Vaginal swabs with a self-sampling procedure for HPV DNA testing in the prevention of cervical cancer

In 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a plan of action to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer caused by Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) through the vaccination and treatment of at least 90% of women by 2030¹.

Much had already been done before the pandemic, through awareness campaigns on the fundamental issue of prevention¹-².

Italy has locally organised screening programmes, which for decades have provided free access to cervical screening/HPV DNA testing for women of 25 to 64 years of age, bringing the incidence of cancer to lower levels than the world average. However, the incidence is not yet at zero, and it is therefore important to maintain high levels of vigilance and to continually improve access and adherence to preventive tests³. As attested by the IARC since 1996, HPV infection is the essential condition for the development of cervical cancer: it is the first cancer to be recognised by the World Health Organisation as being totally attributable to infection. This was discovered in 1976 by Prof. Harald Zur Hausen, who was awarded the Nobel Prize 30 years later, in 2008.

There are approximately 120 types of HPV viruses, but only 12 cause cervical cancer. Testing positive for HPV does not necessarily mean you have cancer at that time, but it does mean you are at greater risk of it developing in the future. Most of these infections resolve spontaneously with no symptoms, but an infection that persists for more than two years can result in precancerous lesions and carcinoma⁴. In 2020, cervical cancer was the fifth most common cancer in women in Italy under 50 years of age(2,400 new cases estimated in 2020, accounting for 1.3% of all cancers affecting the female population⁵.

Eliminating cervical cancer is now a global public health goal launched by the WHO in 2018, and a commitment of the European Union, which has included it in Europe's Beating Cancer Plan⁶. The aim of screening for cervical carcinoma is to detect persistent infections caused by types of viruses that have oncogenic potential, and para-neoplastic lesions, in order to implement appropriate follow-up and treatment before an actual tumour develops³.

Nowadays, it is no longer necessary to see a gynaecologist for HPV testing. Patients can also choose to collect a sample themselves at home and take it to a licensed diagnostic centre, where they will get a clear result quickly in the interests of staying healthy. All under the supervision of a practitioner who will manage follow-up for the woman in the event of a positive result. HPV DNA testing is simple and effective, and women can also collect samples independently thanks to self-sampling procedures using suitable validated⁷-⁸ devices. With self-sampling, which is already practised when screening to prevent colorectal cancer for example, women can collect a sample of cells for HPV DNA testing themselves at home, without having to go to a clinic or gynaecologist, making it even easier to participate in the screening campaign. A number of clinical studies⁹ have been carried out to assess the reliability and accuracy of the results obtained by self-sampling, and both women and practitioners can trust the procedure.

To screen for HPV infection, Becton Dickinson offers BD Onclarity™ HPV test, which is performed in the laboratory on BD Viper™ LT (for small- to medium-sized laboratories) and BD COR™ (for high productivity centralised laboratories) automated platforms. The test fully complies with the European Regulation, being CE IVD marked, and is clinically validated according to the Meijer¹⁰ criteria for applicability in cervical screening using the primary HPV DNA test. The test is CE-IVD validated on specimens collected to additionally perform liquid cytology (cervical screening test) in BD SurePath™ or ThinPrep® vials.

BD Onclarity™ HPV test makes it possible to:

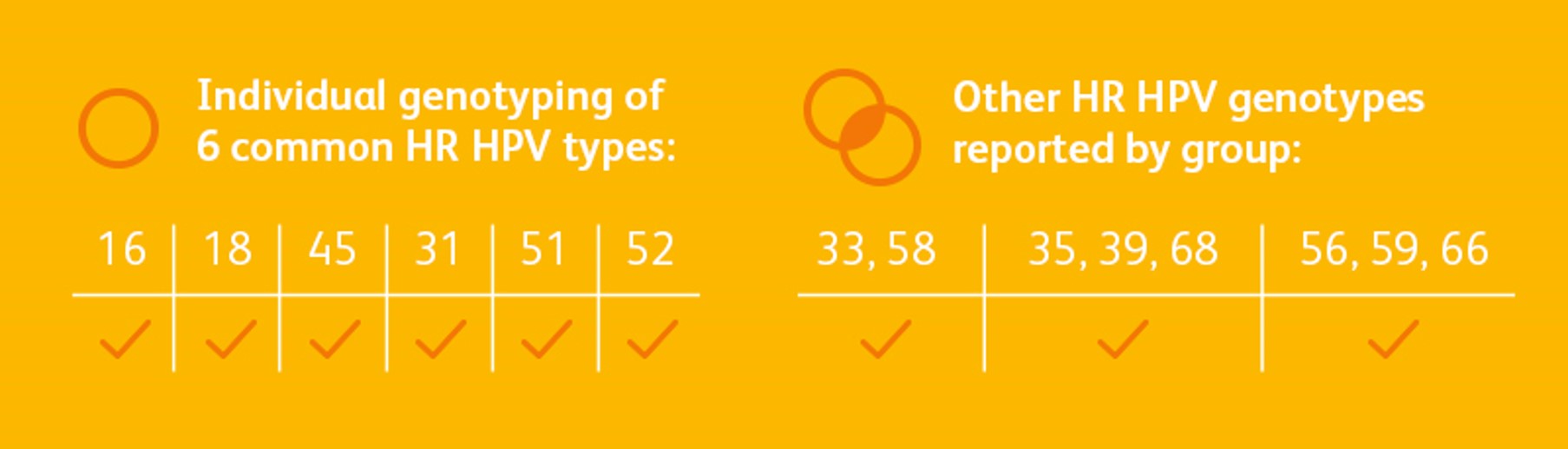

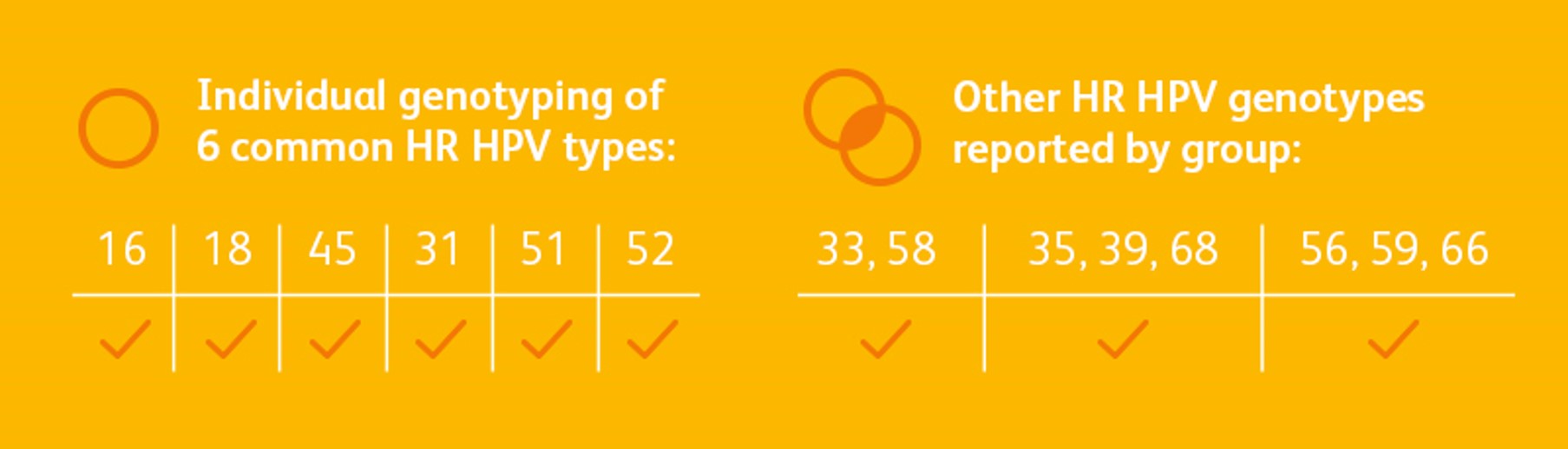

● detect the DNA of the 14 HPV genotypes that carry oncogenic risk (HR- HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) associated with the development of cervical cancer, with the possibility of extended genotyping in addition to HPV genotypes 16 and 18. Six genotypes are genotyped individually, and the remaining are genotyped into 3 different groups (P1, P2 and P3)

● analyse the genes for viral oncoproteins E6 and E7, reducing the risk of false negative results that can be found with DNA analysis in the L1 gene, following the integration of viral DNA into cellular DNA

● reduce false positive results due to cross-reactivity with HPV genotypes with low oncogenic risk

● ensure the detection of possible co-infection by the 14 different genotypes with high oncogenic risk

MUSA™ – Be inspired by simplicity

Out of these assumptions, and the desire of BD to become a pioneer and at the forefront working alongside Italian laboratories and women in supporting women's health and screening against HPV, MUSA™, an initiative created to raise awareness of the importance of cervical cancer prevention through the diagnosis of Human Papillomavirus, has emerged.

In close collaboration with the Italian Diagnostic Center – CDI, MUSA™ promotes the importance of screening as an indispensable weapon with which to fight this disease, thanks also to the innovative HPV Test in self-sampling mode: convenient, easy and effective, which can be used wherever and whenever the patient wishes. By filling in a simple request form, patients can purchase the self-sampling kit, which will be delivered to their home. This enables them to collect a sample for the HPV test independently and send it to the Laboratory by post/courier. This method of sampling was designed to try to maximise and facilitate participation in screening programmes for women who find it difficult or embarrassing to attend a clinic¹¹-¹².

In recent years, clinical studies conducted both in Italy and internationally have sought to determine both the satisfaction of self-collection and the safety and efficacy of the HPV DNA test performed on self-collected samples compared with those collected by a practitioner (gynaecologist/obstetrician). The results confirmed thereliability of self-sampling and a high level of acceptance among women ¹¹-¹².

Do you want to find out more? Click on the banner below and follow MUSA™ on Instagram and Facebook.

BD-83680

References

- Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health probmem. OMS 2020

- European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening. 2015

- Camara H, Zhang Y, Lafferty L, Vallely AJ, Guy R, Kelly-Hanku A. Self-collection for HPV-based cervical screening: a qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2021 Aug 4;21(1):1503.

- Gisci website. https://www.gisci.it/il-nuovo-programma-di-screening-con-il-test-hpv-sostituisce-il-pap-test. Visited 27 February 2022

- Redazione ANSA. https://www.ansa.it/canale_saluteebenessere/notizie/sanita/2022/05/31/hpv-in-italia-quinto-tumore-per-le-donne-under50_364100ce-cd7c-4410-9ca2-e4190785e0da.html Visitato il 01 giugno 2022

- Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan

- Rossi P, Marsili LM, Camilloni L, Iossa A, Lattanzi A, Sani C, Di Pierro C, Grazzini G, Angeloni C, Capparucci P, Pellegrini A, Schiboni ML, Sperati A, Confortini M, Bellanova C, D’Addetta A, Mania E, Visioli CB, Sereno E, Carozzi F. The effect of self-sampled HPV testing on participation to cervical canrcer screening in Italy: a randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN96071600). British Journal of Cancer (2011) 104, 248 – 254.

- Snijders P, Verhoef V, Arbyn M, Ogilvie G, Minozzi S, Banzi R, van Kemenade F, Heideman D, Meijer C. High-risk HPV testing on self-sampled versus clinician-collected specimens: A review on the clinical accuracy and impact on population attendance in cervical cancer screening. International Journal of Cancer (2013) 132(10):2223-36

- Canfell K, Smith MA, Bateson DJ. Self-collection for HPV screening: a game changer in the elimination of cervical cancer. Med J Aust. 2021 Oct 18;215(8):347-348.

- BD Onclarity™ HPV Assay EU Package Insert (8089899).

- Del Mistro A, et al. Efficacy of self-sampling in promoting participation to cervical cancer screening also in subsequent round. Prev Med Rep . 2016 Dec 23;5:166-168. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.12.017. eCollection 2017 Mar

- Arbyn M et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018 Dec 5;363:k4823. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4823.

BACK TO THE NEWS